Despite the growing chasm between India and Pakistan, the passage was opened once again ahead of Guru Nanak’s 552nd birth anniversary

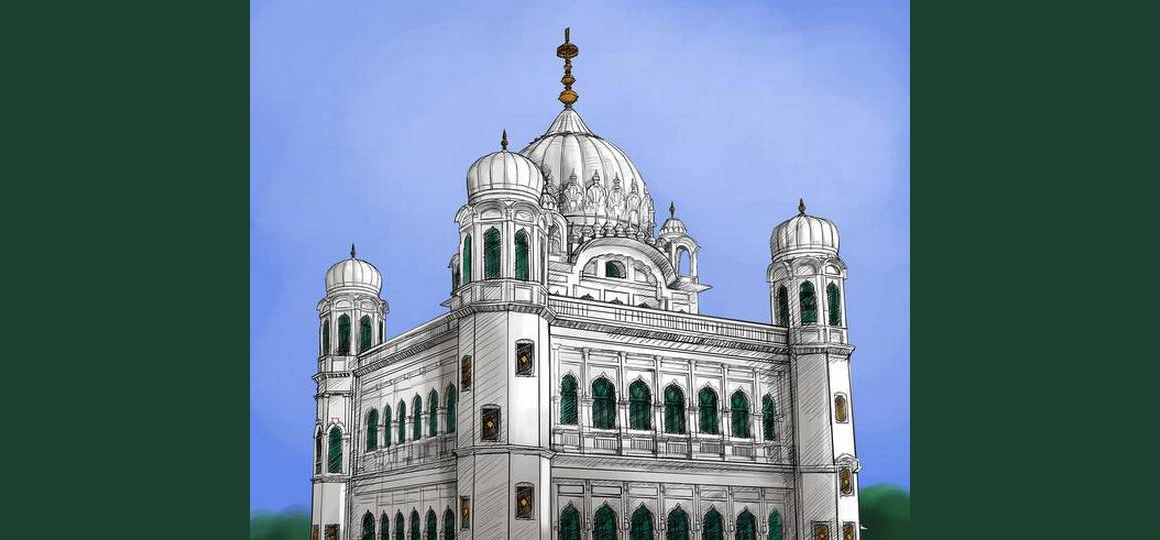

Right by the Ravi river-bed in Pakistan’s Narowal district of Punjab, with hardly a building in the distance on any side, the three-storey Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara is a lonely and unique structure. In 2018, sleepy hamlets nearby awoke to the furious sounds of construction, as Pakistan’s then newly elected Prime Minister Imran Khan accepted an old Indian proposal, revived by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to open a “pilgrim corridor” between the two countries. The corridor would connect the Indian town of Baba Dera Nanak in Gurdaspur district, where the Sikh founder Guru Nanak spent much of his life and the Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara built originally on the spot where he meditated, less than five kilometres away, that had been divided by the thoughtless pen of imperial British officers who wrought India’s partition in 1947.

For more than 70 years, pilgrims would line up at the last border point on the Indian side, to climb a rickety watch-post and view Kartarpur Sahib through a telescope lens. With the number of Sikhs in Pakistan dwindling, and access to Kartarpur quite rough compared with the gurdwara at Guru Nanak’s birth place at Nankana Sahib, the shrine had fallen into disuse. While Sikh “jathas” or groups are given visas as part of an agreement for Hindus and Sikh to religious sites in Pakistan, in exchange for visits by Muslim groups to various mosques and shrines in India, these are hard to come by. This was also true for the larger non-Sikh population that venerates Guru Nanak, a Hindu born in 1469, who brought Hindu and Muslim followers together to found Sikhism with the message of “Ik Onkar” (One God) that he spread in travels far and wide until his death in 1539.

The Gurdwara, small in comparison to the scale of more modern Sikh shrines, has immense spiritual importance, say historians. The idea of the organised Langar, or communal kitchen where rich and poor alike of all faiths can come together to cook, serve and eat a meal, which is a distinctive tradition of the Sikh faith, is believed to have been started here. The shrine is the repository of one of the last copies of the original Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book. In his book (Sketches from a Howdah: Lady Canning’s Tours 1858-1861), Pakistani historian Fakir Syed Aijazuddin recounts how a visiting British dignitary, Lady Canning, was shown the Granth, possibly a first for an outsider in three centuries, which she described it in detail in her 1860 journal as “a thick quarto -sized (approximately 10”X 8”) book written in a peculiar character and language”. According to legend, the original gurdwara by the river also housed a Hindu ‘samadhi’ and a Muslim ‘grave’ of Nanak, as final gesture to uniting his followers who belonged to both faiths and followed in his path as the first Sikhs. In 1947, when Pakistan was carved out of India, the location of the Ravi river decided the gurdwara’s fate was in Pakistan, and Sikhs living in Baba Dera Nanak spoke about how they had to flee their homes on the Pakistani side, not realising that they may never be able to visit their beloved shrine again for decades.

Suicide attack

Back to 2019, and between the decision to lay the foundation stone for the restoration of the 500-year-old gurdwara, the construction of a massive compound around it on the Pakistani side, the departure and arrival building on the Indian side, and the building of a road to carry pilgrims on both sides of the border, a near-conflict broke out between both countries. After a massive suicide bomb attack that killed 40 CRPF soldiers in Pulwama in February 2019, India carried out air strikes on the Pakistani town of Balakot, leading to counter-strikes by Pakistan along the Line of Control.

A few months later, the Modi Government amended Article 370 and bifurcated the State of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories, triggering a series of diplomatic measures by Pakistan, including the recall of High Commissioners, cancelling all trade links and closing its airspace. Conquering the rancour between India and Pakistan was a near impossible feat, and the future of the Kartarpur project, due to be inaugurated in November to mark the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak seemed dim. However, just a few months after exchanging volleys at the UN that year, Mr. Modi and Mr. Khan decided to persevere with the project, and the Kartarpur Corridor was inaugurated on November 9, 2019, allowing the first group of 550 Indian pilgrims to cross over into Pakistan.

The pilgrims did not need a visa, and were allowed into Pakistan by a special arrangement that registers them on the Indian side, and lets them visit Kartarpur for the day. Such international human corridors normally work when there is a natural disaster, a conflict where civilians are caught or a refugee crisis, but Kartarpur is a rare peacetime, pilgrim corridor.

Inaugurating the integrated check post at Baba Dera Nanak, Mr. Modi thanked Mr. Khan and likened the opening of the corridor to the fall of the Berlin Wall, leading many to believe Kartarpur would mark the beginning of other new initiatives between India and Pakistan, rolling back the break in ties. That was not to be. The inauguration of the Gurdwara corridor was marred by the presence of “Khalistani separatist elements”, which New Delhi protested, and security officials said they worried about the corridor being misused for the movement of spies, weapons, cash and drugs, cautioning against increasing the number of pilgrims allowed per day beyond a few hundreds.

Pakistan was willing to raise the number to 10,000, provided they would each pay an entrance fee of $20. India stipulated that each corridor traveller could carry no more than ₹11,000 and a bag weighing no more than 7 kg. Despite all the restrictions and procedural delays with registering for the journey, nearly 45,000 Indians and OCIs (Overseas citizens of India) visited Kartarpur on the corridor in the first two months (by January 31, 2020), an average of about 500 per day.

More trouble

More trouble followed. Within just four months of opening, the corridor had to be closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, as India and Pakistan imposed lockdowns and international travel restrictions. The year that has followed has seen unabated tensions between the two countries, relieved very intermittently by a COVID health initiative for SAARC countries, an LoC ceasefire, an invitation from India to Pakistan for a conference on Afghanistan in Delhi (which was rejected), and an international cricket match between the two countries. Against all odds, and despite the growing chasm between India and Pakistan, Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara and the corridor opened once again on November 17, ahead of Guru Nanak’s 552nd birth anniversary.

“The spirit of Kartarpur continues to live. Centuries after his death, Guru Nanak’s message conquers politics, bridges divides and provides a corridor to mutual humanism,” historian Fakir Aijazuddin told The Hindu, when asked about the reopening, in what most would see as an over-optimistic sentiment given the times.

Today, in the absence of any other new initiative that would bring the two countries closer together, the Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara remains both geographically and metaphorically a unique, lonely structure across a bleak landscape.

Kartarpur Corridor | A pilgrim corridor across a bleak landscape

Despite the growing chasm between India and Pakistan, the passage was opened once again ahead of Guru Nanak’s 552nd birth anniversary

Right by the Ravi river-bed in Pakistan’s Narowal district of Punjab, with hardly a building in the distance on any side, the three-storey Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara is a lonely and unique structure. In 2018, sleepy hamlets nearby awoke to the furious sounds of construction, as Pakistan’s then newly elected Prime Minister Imran Khan accepted an old Indian proposal, revived by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to open a “pilgrim corridor” between the two countries. The corridor would connect the Indian town of Baba Dera Nanak in Gurdaspur district, where the Sikh founder Guru Nanak spent much of his life and the Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara built originally on the spot where he meditated, less than five kilometres away, that had been divided by the thoughtless pen of imperial British officers who wrought India’s partition in 1947.

For more than 70 years, pilgrims would line up at the last border point on the Indian side, to climb a rickety watch-post and view Kartarpur Sahib through a telescope lens. With the number of Sikhs in Pakistan dwindling, and access to Kartarpur quite rough compared with the gurdwara at Guru Nanak’s birth place at Nankana Sahib, the shrine had fallen into disuse. While Sikh “jathas” or groups are given visas as part of an agreement for Hindus and Sikh to religious sites in Pakistan, in exchange for visits by Muslim groups to various mosques and shrines in India, these are hard to come by. This was also true for the larger non-Sikh population that venerates Guru Nanak, a Hindu born in 1469, who brought Hindu and Muslim followers together to found Sikhism with the message of “Ik Onkar” (One God) that he spread in travels far and wide until his death in 1539.

The Gurdwara, small in comparison to the scale of more modern Sikh shrines, has immense spiritual importance, say historians. The idea of the organised Langar, or communal kitchen where rich and poor alike of all faiths can come together to cook, serve and eat a meal, which is a distinctive tradition of the Sikh faith, is believed to have been started here. The shrine is the repository of one of the last copies of the original Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book. In his book (Sketches from a Howdah: Lady Canning’s Tours 1858-1861), Pakistani historian Fakir Syed Aijazuddin recounts how a visiting British dignitary, Lady Canning, was shown the Granth, possibly a first for an outsider in three centuries, which she described it in detail in her 1860 journal as “a thick quarto -sized (approximately 10”X 8”) book written in a peculiar character and language”. According to legend, the original gurdwara by the river also housed a Hindu ‘samadhi’ and a Muslim ‘grave’ of Nanak, as final gesture to uniting his followers who belonged to both faiths and followed in his path as the first Sikhs. In 1947, when Pakistan was carved out of India, the location of the Ravi river decided the gurdwara’s fate was in Pakistan, and Sikhs living in Baba Dera Nanak spoke about how they had to flee their homes on the Pakistani side, not realising that they may never be able to visit their beloved shrine again for decades.

Suicide attack

Back to 2019, and between the decision to lay the foundation stone for the restoration of the 500-year-old gurdwara, the construction of a massive compound around it on the Pakistani side, the departure and arrival building on the Indian side, and the building of a road to carry pilgrims on both sides of the border, a near-conflict broke out between both countries. After a massive suicide bomb attack that killed 40 CRPF soldiers in Pulwama in February 2019, India carried out air strikes on the Pakistani town of Balakot, leading to counter-strikes by Pakistan along the Line of Control.

A few months later, the Modi Government amended Article 370 and bifurcated the State of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories, triggering a series of diplomatic measures by Pakistan, including the recall of High Commissioners, cancelling all trade links and closing its airspace. Conquering the rancour between India and Pakistan was a near impossible feat, and the future of the Kartarpur project, due to be inaugurated in November to mark the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak seemed dim. However, just a few months after exchanging volleys at the UN that year, Mr. Modi and Mr. Khan decided to persevere with the project, and the Kartarpur Corridor was inaugurated on November 9, 2019, allowing the first group of 550 Indian pilgrims to cross over into Pakistan.

The pilgrims did not need a visa, and were allowed into Pakistan by a special arrangement that registers them on the Indian side, and lets them visit Kartarpur for the day. Such international human corridors normally work when there is a natural disaster, a conflict where civilians are caught or a refugee crisis, but Kartarpur is a rare peacetime, pilgrim corridor.

Inaugurating the integrated check post at Baba Dera Nanak, Mr. Modi thanked Mr. Khan and likened the opening of the corridor to the fall of the Berlin Wall, leading many to believe Kartarpur would mark the beginning of other new initiatives between India and Pakistan, rolling back the break in ties. That was not to be. The inauguration of the Gurdwara corridor was marred by the presence of “Khalistani separatist elements”, which New Delhi protested, and security officials said they worried about the corridor being misused for the movement of spies, weapons, cash and drugs, cautioning against increasing the number of pilgrims allowed per day beyond a few hundreds.

Pakistan was willing to raise the number to 10,000, provided they would each pay an entrance fee of $20. India stipulated that each corridor traveller could carry no more than ₹11,000 and a bag weighing no more than 7 kg. Despite all the restrictions and procedural delays with registering for the journey, nearly 45,000 Indians and OCIs (Overseas citizens of India) visited Kartarpur on the corridor in the first two months (by January 31, 2020), an average of about 500 per day.

More trouble

More trouble followed. Within just four months of opening, the corridor had to be closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, as India and Pakistan imposed lockdowns and international travel restrictions. The year that has followed has seen unabated tensions between the two countries, relieved very intermittently by a COVID health initiative for SAARC countries, an LoC ceasefire, an invitation from India to Pakistan for a conference on Afghanistan in Delhi (which was rejected), and an international cricket match between the two countries. Against all odds, and despite the growing chasm between India and Pakistan, Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara and the corridor opened once again on November 17, ahead of Guru Nanak’s 552nd birth anniversary.

“The spirit of Kartarpur continues to live. Centuries after his death, Guru Nanak’s message conquers politics, bridges divides and provides a corridor to mutual humanism,” historian Fakir Aijazuddin told The Hindu, when asked about the reopening, in what most would see as an over-optimistic sentiment given the times.

Today, in the absence of any other new initiative that would bring the two countries closer together, the Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara remains both geographically and metaphorically a unique, lonely structure across a bleak landscape.

NO COMMENT