Afghanistan’s tribal leaders hold huge influence over society and government

In most republics, the head of state is supreme. Thus, it may have seemed unusual when Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani pleaded “helplessness” in making the decision on whether to release 400 Taliban prisoners, and said he would convene a Loya Jirga, a gathering of elders, to deliberate on it. The decision was the final stumbling block in a series of issues the Taliban has held over the government since February, when it signed a peace agreement with the U.S.

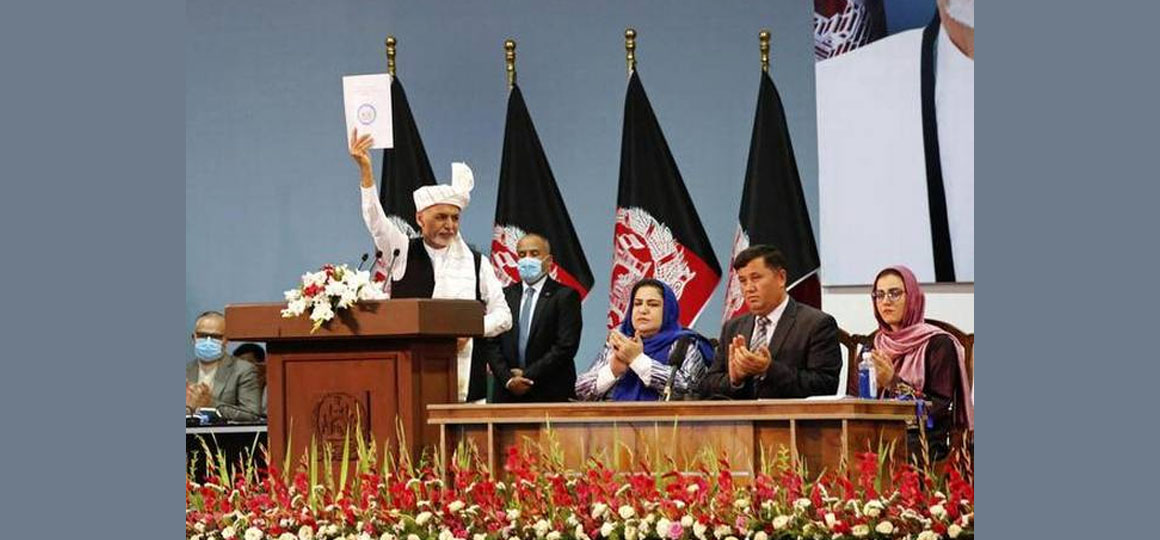

These 400, explained President Ghani’s office, had been convicted of “serious crimes”, and it was not in the President’s “mandate” to pardon or release them. The Loya Jirga of approximately 3,200 representatives from various parts of Afghanistan, including Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras and Uzbeks, met on August 7-9, and directed the release of the men, under the condition they would not return to the battlefield, thus paving the way for the Intra-Afghan negotiations (IAN).

The IAN is now expected to begin in Qatar’s capital Doha later this week, bringing together officials and negotiators of the Ghani government, the High Council for National Reconciliation and civil society representatives face to face with Taliban representatives for the first time. Signing the decree for the release of the last Taliban convicts, Mr. Ghani laid all the credit and responsibility for the decision at the Loya Jirga’s door.

“Today I will sign a decree that I wouldn’t be able to sign in a lifetime, because it was beyond my authority,” Mr. Ghani told the Jirga’s concluding session. “Now, based on your consensus and your moral decision, I will sign the decree on releasing the 400 prisoners and release them.”

The truth is, despite a decade or more of democracy, and years of being a republic, Afghanistan still gives its tradition of Loya Jirgas the kind of respect that allows even an elected head of state to defer to it. Since at least 1709, Jirgas have brought together tribal elders to settle issues of national crises in Afghanistan.

Historical decisions

From the momentous decision to anoint Ahmed Shah Abdali (Durrani) King in 1747, to the historic endorsement of Hamid Karzai as President of the post-Taliban republic, all major decisions in the country flowed from the elders’ conference. Often, it is the leader who turns to the Jirga, as Mr. Ghani just did, when he wants a broader political consensus or a stamp of approval for a policy decision.

“The Loya Jirga is the most powerful constitutional forum [for us]. In fact, the strong legacy of the modern state of Afghanistan derives from this forum,” explained former Afghan Ambassador to India, Shaida Mohammad Abdali, himself a descendent of the former King and a member of the Durrani tribe, when asked about the contradiction inherent in the idea of a democracy taking orders from an unelected body. “The strong legacy of Ahmad Shah Abdali, who founded the modern state of Afghanistan since 1747 lingers on deeply among Afghans till today. Many Jirgas at critical times, and at times of national crisis have been convened and proven extremely effective since then,” he added, referring to the Constitutional Loya Jirga and the Traditional Consultative Loya Jirga which was convened last week.

However, not all Jirgas have endorsed the leader of the times unquestioningly. In 1928, the reformist King Amanullah was setting his country on course for a slew of moves to modernise society — declaring a constitutional monarchy, mandatory schooling for all, abolition of slavery and women’s rights. He convened a Jirga to give its stamp of removal to the measures. However, when he asked his wife Soraiya to remove her veil at a public function, the act led to considerable disquiet during the Jirga. Within the year, a civil war broke out, and King Amanullah was forced into exile.

Many in Afghanistan in modern times have been wary of the Jirga process, which is seen as a patriarchal structure with unlimited powers. In the run-up to the latest Jirga, activists criticised the decision to release Taliban fighters accused of the most heinous crimes as a ‘pre-ordained result’, under pressure from the U.S. government that wants to force the pace of the reconciliation process with the timeline of U.S. Presidential elections in November. U.S. special envoy Zalmai Khalilzad made several trips to Doha, Kabul and Islamabad in the weeks running up to the Jirga, in order to keep plans for the IAN on track. Others, especially women’s rights activists have criticised both the Jirga and its decision to release Taliban prisoners as a regressive step. During the Jirga last week, at least two women representatives were heckled, even assaulted when they tried to voice their protests.

Organisers countered that since 2002, the Jirga has always included women, and the latest one, which is a part of the consultative “Peace Jirga” convened by President Ghani last year to advise the government on the reconciliation process, comprises 30% women, ensuring participation, if not a resounding voice at the centuries old platform.

Loya Jirga | The council of elders

Afghanistan’s tribal leaders hold huge influence over society and government

In most republics, the head of state is supreme. Thus, it may have seemed unusual when Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani pleaded “helplessness” in making the decision on whether to release 400 Taliban prisoners, and said he would convene a Loya Jirga, a gathering of elders, to deliberate on it. The decision was the final stumbling block in a series of issues the Taliban has held over the government since February, when it signed a peace agreement with the U.S.

These 400, explained President Ghani’s office, had been convicted of “serious crimes”, and it was not in the President’s “mandate” to pardon or release them. The Loya Jirga of approximately 3,200 representatives from various parts of Afghanistan, including Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras and Uzbeks, met on August 7-9, and directed the release of the men, under the condition they would not return to the battlefield, thus paving the way for the Intra-Afghan negotiations (IAN).

The IAN is now expected to begin in Qatar’s capital Doha later this week, bringing together officials and negotiators of the Ghani government, the High Council for National Reconciliation and civil society representatives face to face with Taliban representatives for the first time. Signing the decree for the release of the last Taliban convicts, Mr. Ghani laid all the credit and responsibility for the decision at the Loya Jirga’s door.

“Today I will sign a decree that I wouldn’t be able to sign in a lifetime, because it was beyond my authority,” Mr. Ghani told the Jirga’s concluding session. “Now, based on your consensus and your moral decision, I will sign the decree on releasing the 400 prisoners and release them.”

The truth is, despite a decade or more of democracy, and years of being a republic, Afghanistan still gives its tradition of Loya Jirgas the kind of respect that allows even an elected head of state to defer to it. Since at least 1709, Jirgas have brought together tribal elders to settle issues of national crises in Afghanistan.

Historical decisions

From the momentous decision to anoint Ahmed Shah Abdali (Durrani) King in 1747, to the historic endorsement of Hamid Karzai as President of the post-Taliban republic, all major decisions in the country flowed from the elders’ conference. Often, it is the leader who turns to the Jirga, as Mr. Ghani just did, when he wants a broader political consensus or a stamp of approval for a policy decision.

“The Loya Jirga is the most powerful constitutional forum [for us]. In fact, the strong legacy of the modern state of Afghanistan derives from this forum,” explained former Afghan Ambassador to India, Shaida Mohammad Abdali, himself a descendent of the former King and a member of the Durrani tribe, when asked about the contradiction inherent in the idea of a democracy taking orders from an unelected body. “The strong legacy of Ahmad Shah Abdali, who founded the modern state of Afghanistan since 1747 lingers on deeply among Afghans till today. Many Jirgas at critical times, and at times of national crisis have been convened and proven extremely effective since then,” he added, referring to the Constitutional Loya Jirga and the Traditional Consultative Loya Jirga which was convened last week.

However, not all Jirgas have endorsed the leader of the times unquestioningly. In 1928, the reformist King Amanullah was setting his country on course for a slew of moves to modernise society — declaring a constitutional monarchy, mandatory schooling for all, abolition of slavery and women’s rights. He convened a Jirga to give its stamp of removal to the measures. However, when he asked his wife Soraiya to remove her veil at a public function, the act led to considerable disquiet during the Jirga. Within the year, a civil war broke out, and King Amanullah was forced into exile.

Many in Afghanistan in modern times have been wary of the Jirga process, which is seen as a patriarchal structure with unlimited powers. In the run-up to the latest Jirga, activists criticised the decision to release Taliban fighters accused of the most heinous crimes as a ‘pre-ordained result’, under pressure from the U.S. government that wants to force the pace of the reconciliation process with the timeline of U.S. Presidential elections in November. U.S. special envoy Zalmai Khalilzad made several trips to Doha, Kabul and Islamabad in the weeks running up to the Jirga, in order to keep plans for the IAN on track. Others, especially women’s rights activists have criticised both the Jirga and its decision to release Taliban prisoners as a regressive step. During the Jirga last week, at least two women representatives were heckled, even assaulted when they tried to voice their protests.

Organisers countered that since 2002, the Jirga has always included women, and the latest one, which is a part of the consultative “Peace Jirga” convened by President Ghani last year to advise the government on the reconciliation process, comprises 30% women, ensuring participation, if not a resounding voice at the centuries old platform.

NO COMMENT