Ex-Adviser says talks with Taliban indicate options in Afghanistan are narrowing

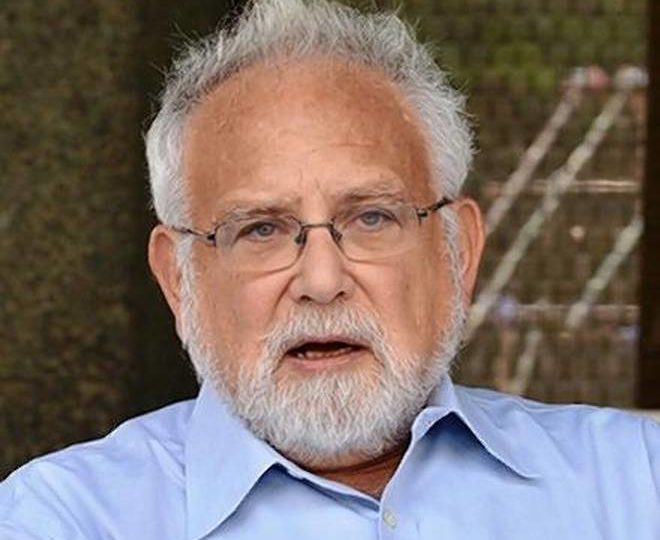

U.S. talks with the Taliban are an indicator that its options in Afghanistan are narrowing, and India and China should seek more avenues of cooperation there for regional stability, says U.S. academic and former senior adviser to the U.S. on Afghanistan and Pakistan, Barnett Rubin.

The U.S. continues to engage with the Taliban, with a second round of talks in Doha recently, despite Taliban escalating violence in Afghanistan. Why?

When you’re at war, you don’t engage your enemy despite the fact that they’re engaging in violence, but because they’re engaging in violence and you want to end it. The U.S. has concluded that its military options have accomplished whatever they are going to accomplish. In addition, the Afghan government has been pushing for talks with the Taliban for sometime.

Remember, the U.S. is far away and Afghanistan is landlocked, so whatever the U.S.’s leadership says about being committed, eventually the U.S. will leave, and we have to prepare the way for that and people in the region need to prepare for a post-American era in Afghanistan.

Despite President Donald Trump’s January 1 tweet threatening Pakistan, nothing appears to have changed in terms of support to terror groups and safe havens. Has the U.S. run out of levers over Pakistan today?

The U.S. has much less leverage over Pakistan now than it ever had before, because Pakistan is so much closer to China, and China is so much bigger than it used to be.

Also, the U.S. still needs access to Afghanistan through Pakistan, because the options — Iran, and the northern route through Russia — are even more difficult as we have put sanctions on both.

We could put sanctions on Pakistan, but only if the U.S. no longer has troops in Afghanistan.

Why do you think the U.S. will pull out eventually?

Because Trump doesn’t want to be there. Most of what he does is motivated by domestic policy. There is no or very little political support in the U.S. to continue fighting in Afghanistan, or to spend billions of dollars there.

The appointment of Zalmay Khalilzad as special envoy for reconciliation is also contrary to the U.S. policy that talks were not essential to the South Asia Policy. I think President Trump has never been enthusiastic about the war in Afghanistan. He gave the military a chance, but has now given them some sort of a deadline, and he doesn’t want to campaign for the 2020 elections with U.S. troops still fighting in Afghanistan.

Has the U.S.’s South Asia Policy, announced more than a year ago, failed?

Well, I think there were two basic flaws in the policy. One, that they called it a regional policy for South Asia. But Afghanistan also borders Central Asia and the Persian Gulf region, and Trump never mentioned Russia, China or Iran. Also, there is this delusion in the U.S. that they can strengthen the Afghan government and get control of 80% of the population, thereby forcing the Taliban to negotiate which just did not succeed. The Afghan government has become weaker too. So in my judgment the South Asia policy has failed. I think President Trump has now looked at the other two options: to privatise the war, which is unacceptable to the Afghan government, and to try and make peace.

You have said that India and China should cooperate further on Afghanistan, but they have fundamental differences over the CPEC/BRI and China’s stand on designating terrorists in Pakistan. Can they overcome those differences?

Both India and China need a stable region to help their big plans for growth. There is a possible railroad project in Afghanistan for a rail link, for example, that Uzbekistan has asked India to participate in, and I think it should be encouraged, as it would effectively connect China to Chabahar and would give China options to Gwadar.

So the India-China conflict should not preclude cooperating from time to time when their interests converge.

NO COMMENT