While piloting foreign policy, he built strong friendships by striking a personal chord in the difficult post-Pokhran period

Jaswant Singh was guided by a view of “India’s destiny”, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar said on Sunday, paying a tribute to the former External Affairs Minister.

“His long view of events was borne from his erudition and understanding of political complexities. If you were to ask, which of my predecessors had influenced me most, that would be Jaswant Singh,” Dr. Jaishankar told The Hindu, speaking of Mr. Singh’s tenure from 1998-2002, an extremely eventful period in Indian foreign policy, whose imprint endures.

Within the first three months of his tenure, Mr. Singh’s most important task was cut out at Pokhran, after India’s nuclear tests in May 1998 — that of restoring India’s ties with the world, particularly the U.S. and Japan who reacted very strongly to the Vajpayee government’s decision.

Mr. Jaishankar, who was India’s Deputy Chief Mission in Tokyo at the time, recalls how Mr. Singh led a difficult mission to Japan in 1999, after the Hashimoto government had frozen all ties for a period of three years, and, along with the U.S., announced a slew of economic sanctions.

“Mr. Singh was directly responsible for the return to normalcy [in ties] starting from his 1999 visit,” recalled Mr. Jaishankar. He added, “In particular, he saw that the key to global acceptance of India’s nuclear status was to gain the U.S.’s acceptance, which he pursued through personal diplomacy.”

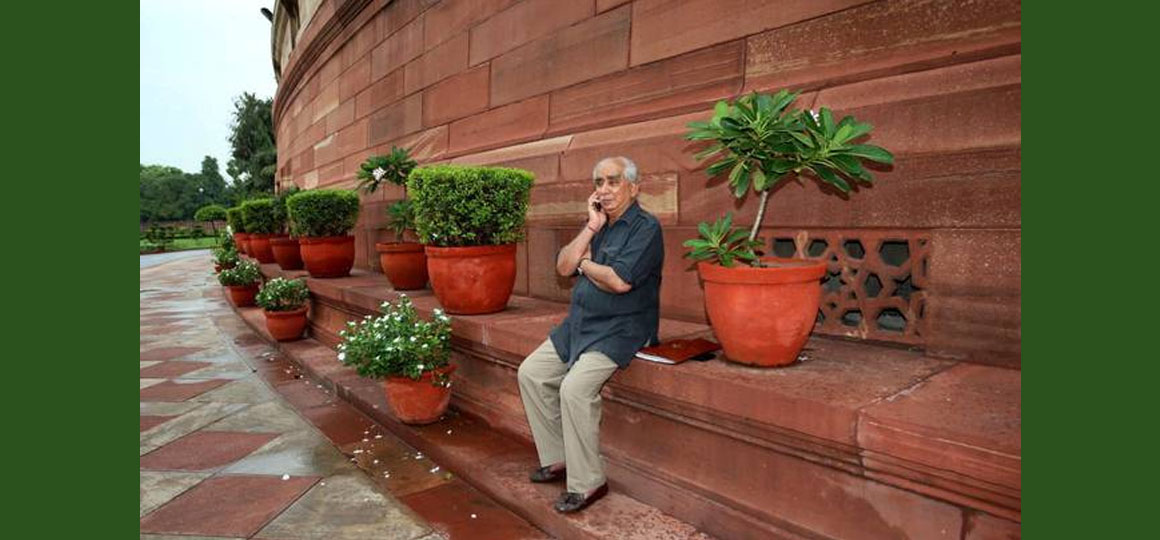

Mr. Singh, formerly a Major in the Indian Army belonging to the Central India Horses cavalry regiment, built strong friendships by striking a personal chord.

His former private secretary in the Finance Ministry, V. Srinivas recalls that his motto was “trust the man, not the paper”.

Reactions to Jaswant Singh’s death | Left a strong mark as a soldier and parliamentarian, says PM Modi

When U.S. President Bill Clinton visited India in 2000, Mr. Singh arranged a visit to his home State of Rajasthan, where Mr. Clinton saw tigers, and played Holi with villagers. With his counterpart in the U.S. (General) Colin Powell, Mr. Singh shared the greeting, “from one soldier to another”.

In his talks with U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott, who was also a good friend, Mr. Singh quite bluntly said the U.S. style of “checklist diplomacy”, based on ticking off a list of specific agreements, clashed terribly with the Indian style of building a mutual understanding, where specifics could be discussed later.

He was candid enough to admit later, that the clash accounted for many disagreements over the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and other Indo-U.S. issues as well.

Another relationship he worked to restore post-Pokhran was with Gulf countries, and particularly Saudi Arabia, through a visit in 2001, when Prince Saud presented him with four Arabian horses. The horses were kept with the President’s Bodyguard (PBG) at Rashtrapati Bhawan, and Mr. Singh was often seen by early morning walkers, riding them. He also became the first Indian Foreign Minister to visit both Israel and Palestine during his tenure.

Even in his most difficult task, that of dealing with Pakistan despite the onslaught of some of the worst terror attacks at the time, the Kargil war, and the military mobilisation during Operation Parakram, Mr. Singh managed to strike a rapport with each of his interlocuters including President Pervez Musharraf.

“He was not a romantic or nostalgic about ties with Pakistan, but his view was that if India wanted to grow in the world, it would have to deal with its neighbour, and keep trying,” explained retired diplomat TCA Raghavan, one of his closest aides, and now now Director of the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA).

In later years, when Mr. Singh was an opposition leader, and Mr. Raghavan the DCM in Islamabad, Mr. Singh decided to travel across the desert from his native Barmer to the Hinglaj Mata temple in Balochistan, along with a hundred Hindu pilgrims. Although the visit was inadvisable, given the rigours of the journey and the unpredictability of ties with Pakistan, Mr. Singh insisted on going. Much to everyone’s surprise, President Musharraf had ordered an entire tent city to be set up in the desert to welcome the travellers from India, and all traditional hospitality provided.

Each day in office ended only after Mr. Singh had meticulously recorded his impressions in a diary. Writing about his most difficult assignment of travelling to Kandahar on December 31, 1999, with three terrorists including Masood Azhar onboard, who were then exchanged for the release of 175 Indian captives aboard flight IC-814, Mr. Singh described a young mother who was a hostage who grabbed his neck and berated him for having “betrayed” them during the week-long hijacking ordeal.

“There was so much criticism of his actions, but he took it on the chin, and accepted the blame on behalf of the government,” Mr. Raghavan said.

In his memoirs, Mr. Singh said “navigating the decidedly stormy diplomatic seas,” was his ‘Call to Honour’.

Diplomacy was Jaswant Singh’s ‘Call to Honour’

While piloting foreign policy, he built strong friendships by striking a personal chord in the difficult post-Pokhran period

Jaswant Singh was guided by a view of “India’s destiny”, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar said on Sunday, paying a tribute to the former External Affairs Minister.

“His long view of events was borne from his erudition and understanding of political complexities. If you were to ask, which of my predecessors had influenced me most, that would be Jaswant Singh,” Dr. Jaishankar told The Hindu, speaking of Mr. Singh’s tenure from 1998-2002, an extremely eventful period in Indian foreign policy, whose imprint endures.

Within the first three months of his tenure, Mr. Singh’s most important task was cut out at Pokhran, after India’s nuclear tests in May 1998 — that of restoring India’s ties with the world, particularly the U.S. and Japan who reacted very strongly to the Vajpayee government’s decision.

Mr. Jaishankar, who was India’s Deputy Chief Mission in Tokyo at the time, recalls how Mr. Singh led a difficult mission to Japan in 1999, after the Hashimoto government had frozen all ties for a period of three years, and, along with the U.S., announced a slew of economic sanctions.

“Mr. Singh was directly responsible for the return to normalcy [in ties] starting from his 1999 visit,” recalled Mr. Jaishankar. He added, “In particular, he saw that the key to global acceptance of India’s nuclear status was to gain the U.S.’s acceptance, which he pursued through personal diplomacy.”

Mr. Singh, formerly a Major in the Indian Army belonging to the Central India Horses cavalry regiment, built strong friendships by striking a personal chord.

His former private secretary in the Finance Ministry, V. Srinivas recalls that his motto was “trust the man, not the paper”.

Reactions to Jaswant Singh’s death | Left a strong mark as a soldier and parliamentarian, says PM Modi

When U.S. President Bill Clinton visited India in 2000, Mr. Singh arranged a visit to his home State of Rajasthan, where Mr. Clinton saw tigers, and played Holi with villagers. With his counterpart in the U.S. (General) Colin Powell, Mr. Singh shared the greeting, “from one soldier to another”.

In his talks with U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott, who was also a good friend, Mr. Singh quite bluntly said the U.S. style of “checklist diplomacy”, based on ticking off a list of specific agreements, clashed terribly with the Indian style of building a mutual understanding, where specifics could be discussed later.

He was candid enough to admit later, that the clash accounted for many disagreements over the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and other Indo-U.S. issues as well.

Another relationship he worked to restore post-Pokhran was with Gulf countries, and particularly Saudi Arabia, through a visit in 2001, when Prince Saud presented him with four Arabian horses. The horses were kept with the President’s Bodyguard (PBG) at Rashtrapati Bhawan, and Mr. Singh was often seen by early morning walkers, riding them. He also became the first Indian Foreign Minister to visit both Israel and Palestine during his tenure.

Even in his most difficult task, that of dealing with Pakistan despite the onslaught of some of the worst terror attacks at the time, the Kargil war, and the military mobilisation during Operation Parakram, Mr. Singh managed to strike a rapport with each of his interlocuters including President Pervez Musharraf.

“He was not a romantic or nostalgic about ties with Pakistan, but his view was that if India wanted to grow in the world, it would have to deal with its neighbour, and keep trying,” explained retired diplomat TCA Raghavan, one of his closest aides, and now now Director of the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA).

In later years, when Mr. Singh was an opposition leader, and Mr. Raghavan the DCM in Islamabad, Mr. Singh decided to travel across the desert from his native Barmer to the Hinglaj Mata temple in Balochistan, along with a hundred Hindu pilgrims. Although the visit was inadvisable, given the rigours of the journey and the unpredictability of ties with Pakistan, Mr. Singh insisted on going. Much to everyone’s surprise, President Musharraf had ordered an entire tent city to be set up in the desert to welcome the travellers from India, and all traditional hospitality provided.

Each day in office ended only after Mr. Singh had meticulously recorded his impressions in a diary. Writing about his most difficult assignment of travelling to Kandahar on December 31, 1999, with three terrorists including Masood Azhar onboard, who were then exchanged for the release of 175 Indian captives aboard flight IC-814, Mr. Singh described a young mother who was a hostage who grabbed his neck and berated him for having “betrayed” them during the week-long hijacking ordeal.

“There was so much criticism of his actions, but he took it on the chin, and accepted the blame on behalf of the government,” Mr. Raghavan said.

In his memoirs, Mr. Singh said “navigating the decidedly stormy diplomatic seas,” was his ‘Call to Honour’.

NO COMMENT