Reporting on back-channel talks is a large part of covering diplomacy

News is a chase, I remember thinking, as we sped down that long, dimly lit road in Sharm El Sheikh, trying to keep up with the Pakistani Foreign Secretary’s car. We had spied him leaving the hotel where the Indian delegation was staying and went in pursuit of the car, hoping to doorstep him into telling us where India-Pakistan negotiations, on the sidelines of the Non-Aligned Movement meet being held at the Egyptian resort town in 2009, were headed. Much of diplomatic coverage means tracking down such meetings behind the scenes and back-channel contacts between governments of countries that aren’t otherwise willing to speak about their bilateral dialogue. Eventually, the Pakistani diplomat rewarded our persistence with an interview, but that was a rare moment of luck. Journalists trying to cover such awkward tête-à-têtes normally find themselves dealing with aggressive security guards, hostile officials, and official denials for their stories.

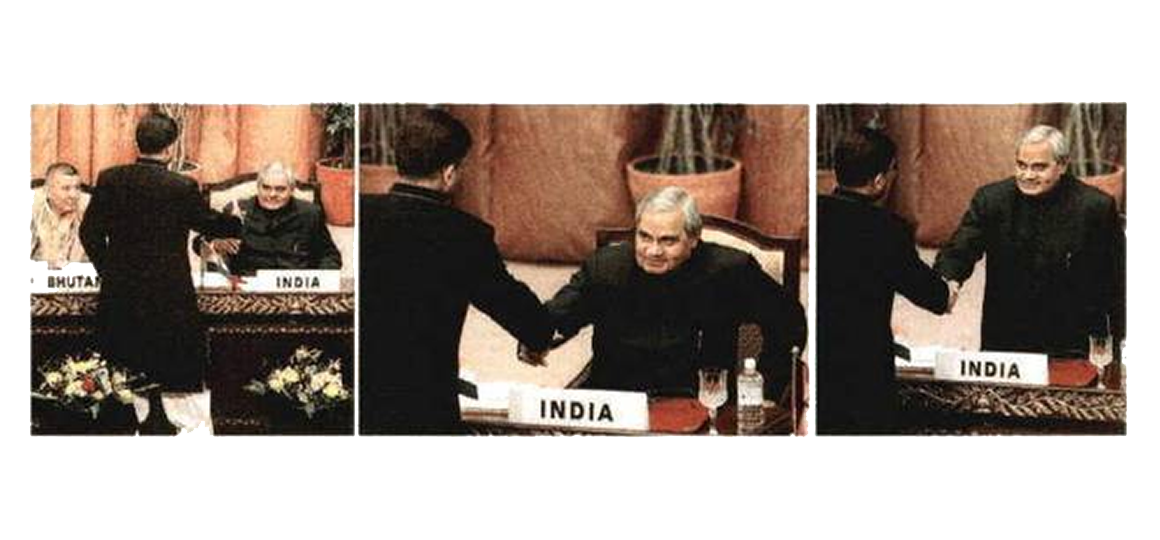

In 2002, I was accosted by an irate posse of Indian officials in Kathmandu for reporting that a meeting had been planned between then Foreign Ministers Jaswant Singh and Sartaj Aziz, on the sidelines of the SAARC summit in progress. Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had just exchanged an unexpected but frosty handshake with Pakistan President General Pervez Musharraf who had walked up to him on stage and practically forced him into the gesture. The event came a month after the Parliament attack, and Indian and Pakistani troops had begun their massive build-up (Op Parakram) at the Line of Control. The officials who met me angrily denied our story and wanted us to retract it. Fortunately we were saved from the dire consequences they threatened us with, when an intrepid Nepali photographer released a photo of the two Foreign Ministers engaged in talks inside the conference hall and even exchanging what appeared to be handwritten notes.

The truth is that such contacts are discovered or reported only a fraction of the time they occur: given security restrictions and shrinking access to official events, journalists have to be very lucky or well sourced to even know that these meetings are taking place. A few years ago, some of the most senior Indian and Pakistani journalists were at a conference in Bangkok, and had no idea that just a few hotels away, National Security Adviser (NSA) Ajit Doval and senior Indian officials were meeting with Pakistani NSA Nasir Janjua and their counterparts. At other times, the chase has been made impossible by logistics: at the SAARC summit in the Maldives, the organisers ensured total privacy by housing all official delegations on a completely different island from the journalists. No boats were made available for us to travel across. Travel restrictions that have followed the COVID-19 pandemic are making the situation more difficult, as reporters covering the recent back-channel contacts between India and Pakistan and India and the Taliban have found out, as despite various officials confirming the meetings, there are no eyewitness accounts of them.

Perhaps the most legendary dodge by interlocutors came about 50 years ago, when U.S. presidential adviser Henry Kissinger went on his secret visit to Beijing to negotiate the opening of U.S.-China diplomatic relations. He went first to Islamabad, just so that he could shake all journalists off his trail, with help from the Pakistani government. During a dinner hosted by President Yahya Khan, Kissinger feigned an illness “due to the heat” and was “invited” to spend a few days in the hill station at Nathia Gali outside Islamabad. Once he was away from the prying eyes of the media, and even his own State Department officials, Kissinger was driven to the tarmac where a Pakistani plane was waiting to fly him to his secret meeting. Operation Marco Polo had just begun.

Tracking down meetings behind the scenes

Reporting on back-channel talks is a large part of covering diplomacy

News is a chase, I remember thinking, as we sped down that long, dimly lit road in Sharm El Sheikh, trying to keep up with the Pakistani Foreign Secretary’s car. We had spied him leaving the hotel where the Indian delegation was staying and went in pursuit of the car, hoping to doorstep him into telling us where India-Pakistan negotiations, on the sidelines of the Non-Aligned Movement meet being held at the Egyptian resort town in 2009, were headed. Much of diplomatic coverage means tracking down such meetings behind the scenes and back-channel contacts between governments of countries that aren’t otherwise willing to speak about their bilateral dialogue. Eventually, the Pakistani diplomat rewarded our persistence with an interview, but that was a rare moment of luck. Journalists trying to cover such awkward tête-à-têtes normally find themselves dealing with aggressive security guards, hostile officials, and official denials for their stories.

In 2002, I was accosted by an irate posse of Indian officials in Kathmandu for reporting that a meeting had been planned between then Foreign Ministers Jaswant Singh and Sartaj Aziz, on the sidelines of the SAARC summit in progress. Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had just exchanged an unexpected but frosty handshake with Pakistan President General Pervez Musharraf who had walked up to him on stage and practically forced him into the gesture. The event came a month after the Parliament attack, and Indian and Pakistani troops had begun their massive build-up (Op Parakram) at the Line of Control. The officials who met me angrily denied our story and wanted us to retract it. Fortunately we were saved from the dire consequences they threatened us with, when an intrepid Nepali photographer released a photo of the two Foreign Ministers engaged in talks inside the conference hall and even exchanging what appeared to be handwritten notes.

The truth is that such contacts are discovered or reported only a fraction of the time they occur: given security restrictions and shrinking access to official events, journalists have to be very lucky or well sourced to even know that these meetings are taking place. A few years ago, some of the most senior Indian and Pakistani journalists were at a conference in Bangkok, and had no idea that just a few hotels away, National Security Adviser (NSA) Ajit Doval and senior Indian officials were meeting with Pakistani NSA Nasir Janjua and their counterparts. At other times, the chase has been made impossible by logistics: at the SAARC summit in the Maldives, the organisers ensured total privacy by housing all official delegations on a completely different island from the journalists. No boats were made available for us to travel across. Travel restrictions that have followed the COVID-19 pandemic are making the situation more difficult, as reporters covering the recent back-channel contacts between India and Pakistan and India and the Taliban have found out, as despite various officials confirming the meetings, there are no eyewitness accounts of them.

Perhaps the most legendary dodge by interlocutors came about 50 years ago, when U.S. presidential adviser Henry Kissinger went on his secret visit to Beijing to negotiate the opening of U.S.-China diplomatic relations. He went first to Islamabad, just so that he could shake all journalists off his trail, with help from the Pakistani government. During a dinner hosted by President Yahya Khan, Kissinger feigned an illness “due to the heat” and was “invited” to spend a few days in the hill station at Nathia Gali outside Islamabad. Once he was away from the prying eyes of the media, and even his own State Department officials, Kissinger was driven to the tarmac where a Pakistani plane was waiting to fly him to his secret meeting. Operation Marco Polo had just begun.

NO COMMENT