Sri Lanka needs all its creditors to come together and give it some breathing space

On July 20, acting President Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected the President of Sri Lanka. The Government of India, which held an all-party meeting on the crisis in the island nation, said that “fiscal prudence and responsible governance” are the lessons to be learnt from the situation in Sri Lanka and that there should not be a “culture of freebies”. India promised to be supportive of Sri Lanka, which is struggling to deal with the devastation caused by the economic crisis. In such a scenario, what must the world, and India in particular, do to help Sri Lanka? Nirupama Rao and D. Subbarao discuss the question in a conversation moderated by Suhasini Haidar. Edited excerpts:

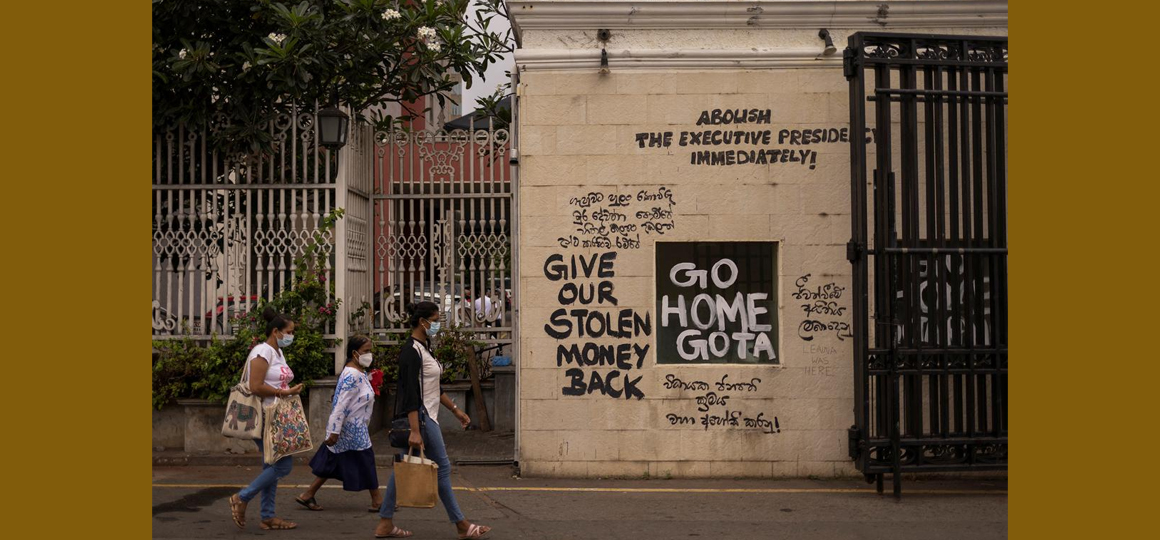

How predictable was the crisis that came to a head in April 2022 with the protests, and how much of the blame lies with the Rajapaksas who have now been pushed out of power?

Nirupama Rao: At the end of the civil war [with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam] in 2009, Sri Lanka had to go to the IMF (International Monetary Fund) for support. Successive governments can be charged with economic mismanagement — fiscal and budgetary — but you can implicate the Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency with a lot of missteps that led the country to where it is now, staring over the economic precipice. What you see now is a perfect storm — economic mismanagement over the years and political malfeasance, which you can lay at the door of the Rajapaksas.

Comment | Helping Sri Lanka more meaningfully

D. Subbarao: The crisis is a consequence of the twin deficit problem: an unsustainable current account deficit and an unsustainable fiscal deficit, some of which they [the Rajapaksas] were not responsible for. Tourism collapsed starting with the Easter bombings, then the pandemic, and remittances from migrant workers declined, again because of the pandemic. The import bill rose because of the war on Ukraine and the spike in oil prices.

On the domestic front, however, the fiscal crisis is completely home-made. The Rajapaksa government gave in to unaffordable populism by cutting taxes. They cut the value added tax by half, eliminated capital gains tax, made expenditure commitments on subsidies that they couldn’t afford, and so debt ballooned. The Rajapaksa government was responsible for three specific things: one, unaffordable populism; two, erratic economic management — for example, the abrupt shift to organic farming; and three, it did not go to the IMF early enough. If it had approached the IMF, say, six months ago, the crisis would not have been as intense.

Do you think global powers could have moved in sooner to try and help at least with the debt repayment deferrals rather than wait for the crisis to have reached the level it has?

D. Subbarao: Sri Lanka’s crisis was so deep that no country by itself could have averted it. And if a country had moved in by itself to solve the problem, it would have taken on more burden without actually solving the crisis. A crisis like this requires IMF assistance, and for other countries to come on board in support of the IMF programme. Take, for example, bilateral debt that Sri Lanka owes to countries such as Japan, China, India. For these countries to reduce or restructure their debt, they will require an IMF programme. So, what countries can do bilaterally is provide a bridge loan, which is what India has done, but the structured solution has to come through the IMF.

Comment | ‘Advantage New Delhi’ in Sri Lanka’s India lifeline

Nirupama Rao: What precipitated the crisis was the big tax holiday that Mr. Gotabaya Rajapaksa gave soon after he assumed office. The balance of payments suffered a great amount of pressure, especially on Sri Lanka’s currency, after COVID. They should have allowed the currency to depreciate, but they spent $5 billion to $6 billion of precious foreign exchange to keep the currency afloat. The advice by the governor of the central bank was a mix of hubris and incompetence and unwillingness to go to the IMF. The President knew nothing about the economy. They followed nationalist economic policies. They kept borrowing from the commercial market. They were not seeking any assistance from the IMF. In fact, they came to India at the end of last year, asking India to reschedule the debt repayment. We had a portfolio of debt of under $1 billion. We wondered why they were coming to us; it was a well-managed portfolio. But they said India is an important partner and that’s why they were coming here. India’s help has been unprecedented. No other country has really come to Sri Lanka’s rescue.

Do you think India’s assistance to Sri Lanka of about $3.8 billion was adequate and timely? How do you evaluate China’s role, which owns at least 10% of Sri Lankan debt?

D. Subbarao: The Indian Government by itself cannot solve Sri Lanka’s problem. Sri Lanka needs everybody who it owes debt to — the IMF, the World Bank, the ADB (Asian Development Bank) and all other partners — to come together and give it some breathing space. That’s what India tried to provide. India could not have restructured all its loans or given all the money that Sri Lanka wanted. India gave aid on time and in sufficient quantity for Sri Lanka to get some breathing space in order to approach the IMF and reach an arrangement with the IMF.

On China’s involvement, Sri Lanka’s debt problem has two egregious sins. One is over-dependence on one country for a bilateral partner, China. The second is the sovereign borrowing in a foreign currency. Given that many of these loans went into infrastructure projects that have taken too long or have been underutilised, debt has piled up, but there are no revenues to repay for it. To that extent, China is responsible for loading on debt, irresponsible lending, and now responsible for not coming soon enough to Sri Lanka’s aid.

Nirupama Rao: India’s help has been unprecedented — other countries have come up with very small amounts of humanitarian assistance at the very most. You may argue that countries like Japan could do more. But if you see the record of the Rajapaksa government, it was very cavalier and churlish in its treatment of Japan over the last few years, by cancelling projects. Japan has every reason to be upset about the way the relationship with Sri Lanka has developed over the last few years.

You mentioned 10% of Sri Lanka’s debt being held by China, but that figure is understated. There’s much more hidden debt held by Chinese entities. Meanwhile, returns on Chinese projects have not added much value to the economy. The 99-year lease of the Hambantota Port was concluded without settling the loans owed to China, and now they are incurring recurring expenditure for running the port. So, that has been a white elephant. The Chinese want more control in Sri Lanka, they want an FTA (Free Trade Agreement), but Chinese goods already flood the market.

Are there other alternatives to the IMF that India should be tapping or helping Sri Lanka to tap? Should India now be looking to use its own resources in a regional fashion and can India even do that?

D. Subbarao: Well, we’ve been struggling with this question for the last 25 years. Countries around the world have been trying to find an alternative to the IMF, because of the concern that IMF conditionality is too harsh and does not result in long-term structural adjustment. But nothing has proved to be an adequate substitute for the IMF — neither bilateral arrangements nor the regional ones. The fact is that if a country is under an IMF programme, external investors, external creditors become confident that they can go back into the country. And that’s why I keep saying that Sri Lanka should have gone to the IMF sooner so that that confidence levels would not have sunk.

Janatha Aragalaya | The movement that booted out the Rajapaksas

Nirupama Rao: Sri Lanka has to go to the IMF, but even that has problems. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman made a strong case for Sri Lanka to be classified temporarily as a low-income country so that it can get assistance on a more emergency basis from the IMF and on the lines of what has been provided to Ukraine. But that has not happened. Sri Lanka has not been able to reach a staff-level agreement with the IMF. It has to legislate decisions on the taxation and revenue side, but it is not able to move in Parliament on that front, given the political crisis. Even the fundamental assessment of debt sustainability has not been reached with the IMF.

What is worrying is that [in this crisis], a fertile ground could be provided for extremist ideologies. The capacity of the country to ensure its maritime security will also suffer and there is a scenario of drugs and arms smuggling staring us in the face. India has to consider how far it can go to help Sri Lanka; I don’t know if the government has taken that decision yet. But we must remember that economic and security factors are interlinked. Maybe the thrust in India should be to look at more regionalising factors when it comes to trade and whether regionalisation of the Indian rupee can be of help to us and our neighbours.

To what extent is the situation in Sri Lanka comparable to that in Indian States, if not the entire economy? External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar’s presentation to parliamentarians seemed to indicate worry about a “spillover” effect.

D. Subbarao: The fact is fiscal profligacy and fiscal irresponsibility will invariably end in tears. Some Indian States are borrowing money and using it on freebies, which do not add to productivity or future economic activity or production capacity, but add to current consumption. So, they do not support long-term growth. But beyond that, States in India cannot be compared to Sri Lanka because Sri Lanka is an independent economic entity whereas the States in India are part of a national economic entity. States in India do not have their own balance of payments, they do not have debt denominated in external currency like Sri Lanka. Second, Sri Lanka can deal with domestic debt by printing currency, as it did, but States in India cannot do that. So, it’s important for us, as the Prime Minister said, to get this into public conversation about whether States and even the Centre should continue to spend money like this on transfer payments and freebies instead of spending on infrastructure that supports long-term growth and employment generation. I don’t believe the Centre and the States should talk about these decisions in an adversarial manner, but agree on some norms. The Supreme Court has also said there must be some norms about how much can be spent on freebies. Politicians might take umbrage, but we must get it right.

Equally, the worries come from not just India but the rest of the neighbourhood. How can India prepare for crises in the rest of South Asia?

Nirupama Rao: A lot has been written about the economic crisis facing Pakistan and Nepal. We should be looking hard at Nepal because Nepal is tied to us in many ways. But one redeeming factor is that Nepal’s currency is pegged to ours and its trade being landlocked, it is completely dependent on India. The issue of regionalisation of the Indian rupee should be looked at more closely. If we apply the regionalisation of our rupee, make it possible for us to trade in rupees with Sri Lanka, it will help Sri Lanka save on hard currency. The digital interface payments that we have, like BHIM, can be used in countries in the neighbourhood such as Nepal and Bhutan. With Sri Lanka, those discussions have not been able to go forward.

What can the world do to help Sri Lanka?

Sri Lanka needs all its creditors to come together and give it some breathing space

On July 20, acting President Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected the President of Sri Lanka. The Government of India, which held an all-party meeting on the crisis in the island nation, said that “fiscal prudence and responsible governance” are the lessons to be learnt from the situation in Sri Lanka and that there should not be a “culture of freebies”. India promised to be supportive of Sri Lanka, which is struggling to deal with the devastation caused by the economic crisis. In such a scenario, what must the world, and India in particular, do to help Sri Lanka? Nirupama Rao and D. Subbarao discuss the question in a conversation moderated by Suhasini Haidar. Edited excerpts:

How predictable was the crisis that came to a head in April 2022 with the protests, and how much of the blame lies with the Rajapaksas who have now been pushed out of power?

Nirupama Rao: At the end of the civil war [with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam] in 2009, Sri Lanka had to go to the IMF (International Monetary Fund) for support. Successive governments can be charged with economic mismanagement — fiscal and budgetary — but you can implicate the Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency with a lot of missteps that led the country to where it is now, staring over the economic precipice. What you see now is a perfect storm — economic mismanagement over the years and political malfeasance, which you can lay at the door of the Rajapaksas.

Comment | Helping Sri Lanka more meaningfully

D. Subbarao: The crisis is a consequence of the twin deficit problem: an unsustainable current account deficit and an unsustainable fiscal deficit, some of which they [the Rajapaksas] were not responsible for. Tourism collapsed starting with the Easter bombings, then the pandemic, and remittances from migrant workers declined, again because of the pandemic. The import bill rose because of the war on Ukraine and the spike in oil prices.

On the domestic front, however, the fiscal crisis is completely home-made. The Rajapaksa government gave in to unaffordable populism by cutting taxes. They cut the value added tax by half, eliminated capital gains tax, made expenditure commitments on subsidies that they couldn’t afford, and so debt ballooned. The Rajapaksa government was responsible for three specific things: one, unaffordable populism; two, erratic economic management — for example, the abrupt shift to organic farming; and three, it did not go to the IMF early enough. If it had approached the IMF, say, six months ago, the crisis would not have been as intense.

Do you think global powers could have moved in sooner to try and help at least with the debt repayment deferrals rather than wait for the crisis to have reached the level it has?

D. Subbarao: Sri Lanka’s crisis was so deep that no country by itself could have averted it. And if a country had moved in by itself to solve the problem, it would have taken on more burden without actually solving the crisis. A crisis like this requires IMF assistance, and for other countries to come on board in support of the IMF programme. Take, for example, bilateral debt that Sri Lanka owes to countries such as Japan, China, India. For these countries to reduce or restructure their debt, they will require an IMF programme. So, what countries can do bilaterally is provide a bridge loan, which is what India has done, but the structured solution has to come through the IMF.

Comment | ‘Advantage New Delhi’ in Sri Lanka’s India lifeline

Nirupama Rao: What precipitated the crisis was the big tax holiday that Mr. Gotabaya Rajapaksa gave soon after he assumed office. The balance of payments suffered a great amount of pressure, especially on Sri Lanka’s currency, after COVID. They should have allowed the currency to depreciate, but they spent $5 billion to $6 billion of precious foreign exchange to keep the currency afloat. The advice by the governor of the central bank was a mix of hubris and incompetence and unwillingness to go to the IMF. The President knew nothing about the economy. They followed nationalist economic policies. They kept borrowing from the commercial market. They were not seeking any assistance from the IMF. In fact, they came to India at the end of last year, asking India to reschedule the debt repayment. We had a portfolio of debt of under $1 billion. We wondered why they were coming to us; it was a well-managed portfolio. But they said India is an important partner and that’s why they were coming here. India’s help has been unprecedented. No other country has really come to Sri Lanka’s rescue.

Do you think India’s assistance to Sri Lanka of about $3.8 billion was adequate and timely? How do you evaluate China’s role, which owns at least 10% of Sri Lankan debt?

D. Subbarao: The Indian Government by itself cannot solve Sri Lanka’s problem. Sri Lanka needs everybody who it owes debt to — the IMF, the World Bank, the ADB (Asian Development Bank) and all other partners — to come together and give it some breathing space. That’s what India tried to provide. India could not have restructured all its loans or given all the money that Sri Lanka wanted. India gave aid on time and in sufficient quantity for Sri Lanka to get some breathing space in order to approach the IMF and reach an arrangement with the IMF.

On China’s involvement, Sri Lanka’s debt problem has two egregious sins. One is over-dependence on one country for a bilateral partner, China. The second is the sovereign borrowing in a foreign currency. Given that many of these loans went into infrastructure projects that have taken too long or have been underutilised, debt has piled up, but there are no revenues to repay for it. To that extent, China is responsible for loading on debt, irresponsible lending, and now responsible for not coming soon enough to Sri Lanka’s aid.

Nirupama Rao: India’s help has been unprecedented — other countries have come up with very small amounts of humanitarian assistance at the very most. You may argue that countries like Japan could do more. But if you see the record of the Rajapaksa government, it was very cavalier and churlish in its treatment of Japan over the last few years, by cancelling projects. Japan has every reason to be upset about the way the relationship with Sri Lanka has developed over the last few years.

You mentioned 10% of Sri Lanka’s debt being held by China, but that figure is understated. There’s much more hidden debt held by Chinese entities. Meanwhile, returns on Chinese projects have not added much value to the economy. The 99-year lease of the Hambantota Port was concluded without settling the loans owed to China, and now they are incurring recurring expenditure for running the port. So, that has been a white elephant. The Chinese want more control in Sri Lanka, they want an FTA (Free Trade Agreement), but Chinese goods already flood the market.

Are there other alternatives to the IMF that India should be tapping or helping Sri Lanka to tap? Should India now be looking to use its own resources in a regional fashion and can India even do that?

D. Subbarao: Well, we’ve been struggling with this question for the last 25 years. Countries around the world have been trying to find an alternative to the IMF, because of the concern that IMF conditionality is too harsh and does not result in long-term structural adjustment. But nothing has proved to be an adequate substitute for the IMF — neither bilateral arrangements nor the regional ones. The fact is that if a country is under an IMF programme, external investors, external creditors become confident that they can go back into the country. And that’s why I keep saying that Sri Lanka should have gone to the IMF sooner so that that confidence levels would not have sunk.

Janatha Aragalaya | The movement that booted out the Rajapaksas

Nirupama Rao: Sri Lanka has to go to the IMF, but even that has problems. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman made a strong case for Sri Lanka to be classified temporarily as a low-income country so that it can get assistance on a more emergency basis from the IMF and on the lines of what has been provided to Ukraine. But that has not happened. Sri Lanka has not been able to reach a staff-level agreement with the IMF. It has to legislate decisions on the taxation and revenue side, but it is not able to move in Parliament on that front, given the political crisis. Even the fundamental assessment of debt sustainability has not been reached with the IMF.

What is worrying is that [in this crisis], a fertile ground could be provided for extremist ideologies. The capacity of the country to ensure its maritime security will also suffer and there is a scenario of drugs and arms smuggling staring us in the face. India has to consider how far it can go to help Sri Lanka; I don’t know if the government has taken that decision yet. But we must remember that economic and security factors are interlinked. Maybe the thrust in India should be to look at more regionalising factors when it comes to trade and whether regionalisation of the Indian rupee can be of help to us and our neighbours.

To what extent is the situation in Sri Lanka comparable to that in Indian States, if not the entire economy? External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar’s presentation to parliamentarians seemed to indicate worry about a “spillover” effect.

D. Subbarao: The fact is fiscal profligacy and fiscal irresponsibility will invariably end in tears. Some Indian States are borrowing money and using it on freebies, which do not add to productivity or future economic activity or production capacity, but add to current consumption. So, they do not support long-term growth. But beyond that, States in India cannot be compared to Sri Lanka because Sri Lanka is an independent economic entity whereas the States in India are part of a national economic entity. States in India do not have their own balance of payments, they do not have debt denominated in external currency like Sri Lanka. Second, Sri Lanka can deal with domestic debt by printing currency, as it did, but States in India cannot do that. So, it’s important for us, as the Prime Minister said, to get this into public conversation about whether States and even the Centre should continue to spend money like this on transfer payments and freebies instead of spending on infrastructure that supports long-term growth and employment generation. I don’t believe the Centre and the States should talk about these decisions in an adversarial manner, but agree on some norms. The Supreme Court has also said there must be some norms about how much can be spent on freebies. Politicians might take umbrage, but we must get it right.

Equally, the worries come from not just India but the rest of the neighbourhood. How can India prepare for crises in the rest of South Asia?

Nirupama Rao: A lot has been written about the economic crisis facing Pakistan and Nepal. We should be looking hard at Nepal because Nepal is tied to us in many ways. But one redeeming factor is that Nepal’s currency is pegged to ours and its trade being landlocked, it is completely dependent on India. The issue of regionalisation of the Indian rupee should be looked at more closely. If we apply the regionalisation of our rupee, make it possible for us to trade in rupees with Sri Lanka, it will help Sri Lanka save on hard currency. The digital interface payments that we have, like BHIM, can be used in countries in the neighbourhood such as Nepal and Bhutan. With Sri Lanka, those discussions have not been able to go forward.

NO COMMENT