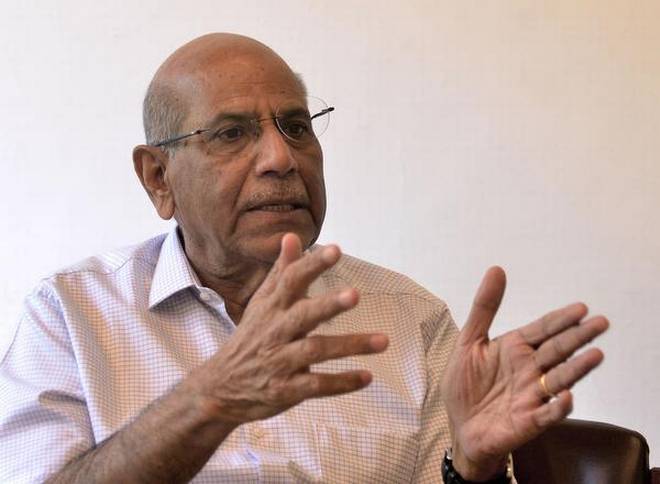

The former Foreign Secretary on the difficult waters in which India must chart its independent strategic trajectory.

At a time when India’s relationships with big powers like the U.S., Russia, China and Europe are increasingly being complicated by their rivalries with each other, the country needs to follow its traditional policy of strategic autonomy, focussing on its own vital interests, says Shyam Saran, former Foreign Secretary and former Chairman of the National Security Advisory Board. Excerpts:

During President Vladimir Putin’s recent visit, India and Russia concluded a big $5 billion deal. But other than defence purchases, have ties lost their depth?

Yes, the most important peg for the relationship continues to be defence purchases and technology. Russia is willing to share things that are not available from other sources — for example, submarine technologies. It was a very well-considered decision for India to go ahead with the S-400 deal, which is one of the most effective missile systems — also because this cements our relationship further as it is a long-term platform.

It is true that something that could have also been a more important part of the relationship — energy — has not really taken off, apart from a few licences and explorations announced. But the bigger substance of the relationship is strategic. If you agree that for the foreseeable future, India’s main challenge is going to be China and how it is reshaping the region and global landscape, then Russia will always be an important partner…

What will be the impact on ties with the U.S.? Hasn’t the field changed drastically given that closer ties with Russia now attract sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act?

The U.S. hasn’t formally given India a waiver, but I think given that India is a major purchaser of U.S. military hardware, and that those [the purchases] are expanding, the U.S. won’t want to undercut its relationship. Even if waivers come per transaction, it would make sense for the U.S. to waive sanctions. We are dealing with an unpredictable U.S. President, so we can’t be sure of anything, and the decision is in his hands, but if rational choices are being made, then it doesn’t help the U.S. to punish India for this purchase.

In May, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj said India recognises UN sanctions, not country-specific sanctions. So, should India even apply for waivers, given that they will come with the condition that India must reduce its ties with Russia?

I don’t think it is necessary to stand too much on principle, since the Americans know our stand. But in real life, we need to make calculations on the risk-benefit ratio, and the risk of waivers is somewhat less.

I ask because a few days after the S-400 deal, India announced that it will purchase oil from Iran past the U.S. deadline date of November 4. Given both these situations, is India at an inflection point?

I would see it as more nuanced. There could be a lower volume of purchases of oil from Iran, which may be enough to indicate to the U.S. that we take their concerns on board. But they can’t expect India to do something that harms [our] own economic interests. From the experience of the last time there were sanctions on Iran oil purchases (2012-2013), the government had an option to circumvent these sanctions through a rupee-rial mechanism or through banks that don’t have exposure to the U.S., and my sense is we will use them this time around too.

What about the U.S. contention that it has stood by India when it comes to concerns over terrorism from Pakistan, and that it is now time for India to stand by the U.S. when it comes to what it alleges is terrorism from Iran?

Whether it is the U.S., China or Russia, each one will try to push India in a direction it likes and it is for us to make our decision on how to balance these contrary pressures, and it is possible to do so. India will be an important component of the reshaping of the world, and we have room for manoeuvre and to expand our strategic space.

India is, in fact, working with all world powers: the U.S., the European Union, Russia and China, but they all seem to have developed tensions with each other. Is this uncharted territory?

We have faced these pulls and pressures all along, and India now has more economic and military power than in the past and can play a more strategic game. It makes no sense for the U.S. and the EU to isolate Russia in the long term, as China is likely to be the bigger challenge. In fact, there seems to be a lowering of Russia’s profile in the “rogues’ gallery”, and a greater focus on China in the last few months. One cannot discount the close trade engagement between the U.S. and China, but this is a trend that bears watching, which also has a positive impact on India-China ties. Whenever there is a rise in U.S.-China tensions, we have seen a lowering of tensions between India and China.

On the India-China front, the last year has seen, as you said, a lowering of tensions, especially after the Wuhan summit. It is also seen as a period when India has conceded to China on several issues: a lower profile for the Tibetan movement and the Dalai Lama; backing away from the ‘Quad’ concept; and, at Doklam, turning a blind eye while the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) builds up infrastructure and stations more troops. Have better ties come at a cost?

Look, there is an expanding asymmetry of power between China and India… Where India sees its interests undermined by Chinese actions it must react, but not necessarily provoke a situation of conflict. On the Tibet issue, let us remember that for decades we followed a certain formulaic policy. The departure came when the Narendra Modi government decided to invite [the Sikyong, the head of the Tibetan government-in-exile] Lobsang Sangay to the Prime Minister’s swearing-in and give the Dalai Lama’s visit to Tawang an official status, while the Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister referred to [the State’s] boundary with “Tibet, not China”.

So, actions taken, by design or inadvertently, gave the impression that India was moving away from what had been our consistent policy. Now, the government has returned to that old policy, because their policy was not sustainable, given the asymmetry. Coming back to our consistent policy was prudent, in my opinion. On Doklam, our agreement was limited to disengagement at the stand-off point. So, the Chinese have moved from what was a transient presence to a more permanent presence by the PLA. And on the road-building, they agreed to stop extending the road ahead to areas considered sensitive for India. So limited gains, but not insignificant ones.

What about the Quad? India appears to be shying away from the formation in which it was seen earlier as a countervailing balance to China in the Indo-Pacific.

Even when we first spoke about the Quad (in 2005), India was cautious about the idea, because we didn’t want to give the sense that we were setting up a military alliance against China in the Indo-Pacific. The tsunami relief gave India a high naval profile as a country that showed a swift maritime response to the crisis, and the U.S. floated the idea of four democracies working together for a consultative forum. The Chinese objected even then, and my counterparts accused India of setting up an “Asian NATO”, and we made it clear that we could choose the forums we wanted even if China didn’t like it, but we did not propose a military alliance directed against anyone. But then the U.S. decided it needed China’s support on North Korea talks and Iran sanctions, and then the Australians pulled away and so the Quad vanished.

This time around we are once again interested in the consultative forum but not in taking it past the military threshold. If this is about the Indo-Pacific, then India has also made it clear that ASEAN is central to any discussion on the region, which stretches from the far east to Africa, as Prime Minister Modi said at his Shangri La dialogue speech this year.

In that speech, the Prime Minister also referred to the term ‘strategic autonomy’, the first time he spoke of it since 2014. Like the China policy, do you think the government is now returning to the concept of ‘strategic autonomy’ as its foreign policy template?

I think one should not just look at the Indian dimension when judging this, but at the global dimension which is influencing it. For starters, India is responding to a very different stand from China on many issues, if you compare the period from 2005 to 2007 with 2015-2017. It is a China far more committed to its investment in Pakistan.

At the Nuclear Suppliers Group in 2007, China didn’t want to come out openly to oppose the nuclear waiver for India, but in 2016, they were proudly proclaiming that they blocked India’s NSG membership and there was nothing we could do about it.

Even on areas of convergent interests like climate change, a decade ago they worked with India, even conceding the leadership on the climate change negotiations. At the Paris summit, in contrast, they dealt directly with the U.S. to strike a deal and didn’t consult us. So, the change is that China now benchmarks itself with the U.S., and doesn’t look to emerging countries as much. And, at the same time, the U.S. is very different too.

We are responding to this different behaviour by working with all our options. I think the decision to sign the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) with the U.S. [in September] was a significant decision and means that India is not slowing down on its desire to strengthen its security relationship with the U.S.

So the stronger and more diversified relations India has with all the major powers, [the more it] helps us deal with our challenges. Strategic autonomy is simply India’s ability to take relatively autonomous decisions on matters of vital interest to us. Not 100% autonomous, but on those decisions that are critical for India, we ensure that they are taken here [New Delhi], not in some other capital. From that point of view, there is continuity today in our foreign policy with how it has always been.

NO COMMENT